From Ojai, I was driving North on California’s Highway 101, first along the glistening Pacific Ocean and then through golden hills, lush green growing fields, and fruit tree groves. I passed the strawberries you ate for breakfast the following month, the lettuce in your salad, and the celery you sautéed for soup.

My destination was the Santa Maria-Bonita School District headquarters where I was scheduled to give three presentations: a workshop to teachers, a speech to parents of English-speaking students, and a speech (in Spanish) to parents of Spanish-speaking students. As I made my way through the long and rewarding day, my colleagues and I were gratified that the Spanish-speaking families comprised the largest audience, filling hundreds of chairs with joy and expectation.

Several years prior, that room would have been nearly empty.

Though the Santa Maria-Bonita School District’s Latino enrollment is now over 95%, the district once had few such students in its gifted program. Many of the area’s migrant families come to California seasonally to work in agriculture, and almost 50% of the district’s students are considered English Language Learners (ELLs). This presents a major challenge for teachers who are responsible for recommending students for the gifted program: a language barrier.

Usually teachers base their recommendations on academic achievement. But if kids don’t speak the language to begin with, how can they spot their smarts? My colleagues began to make changes to rectify the situation and found incredible success engaging Latino families and training teachers to identify the thinking strengths even in ELLs who were not yet fluent in English.

Following a years-long deliberate effort, the gifted program more closely mirrored the demographic make-up of the district. We used the district’s case study, coupled with in-depth research, to create a guide for all schools facing this challenge when we wrote the book Discovering and Developing Talents in Spanish-Speaking Students, published in 2012 by Corwin Press, a division of SAGE.

As is often the case, solving this problem of unrecognized strengths for an outlier group helped make life better for all. One challenge ELLs face is that they are not only underrepresented in gifted programs, but also they are overrepresented in special education programs.

As you may know from my writings, this is true for deep souls as well. The more fortunate deep souls who were placed in special education programs were later switched into gifted programs. Others remained in special ed, wondering exactly why they were there compared to other students who had evident disabilities that needed support.

While writing Discovering and Developing Talents in Spanish-Speaking Students, I took my first deep dive into the research pioneered by E. Paul Torrance who in the 1950s started studying what he called the “creative positives” of disadvantaged youth. Even back then schools were failing minority and poor students. After working with these students for five years, Torrance published a list of strengths that he observed in these children when their strengths were engaged.

Teachers in the Santa Maria-Bonita schools were trained to observe these strengths in their ELL students, leading them to recommend Latinos to the gifted program at a much higher rate. This meant that these children’s strengths were at minimum acknowledged and, at best, supported. It also meant they weren’t misplaced in special education due to their outlier thinking.

Torrance’s Creative Positives:

Ability to express feelings and emotions.

Ability to improvise with commonplace materials.

Articulateness in role playing and storytelling.

Enjoyment of and ability in visual arts, such as drawing, painting, and sculpture.

Enjoyment of and ability in creative movement, dance, and dramatics.

Enjoyment of and ability in music and rhythm.

Use of expressive speech.

Fluency and flexibility in nonverbal media.

Enjoyment of and skills in group activities and problem solving.

Responsiveness to the concrete (i.e., hands-on/tactile).

Responsiveness to the kinesthetic.

Expressiveness of gestures and body languages, and ability to interpret body language.

Humor and sense of humor.

Richness of imagery in informal language.

Originality of ideas in problem solving.

Problem centeredness or persistence in problem solving.

Emotional responsiveness.1

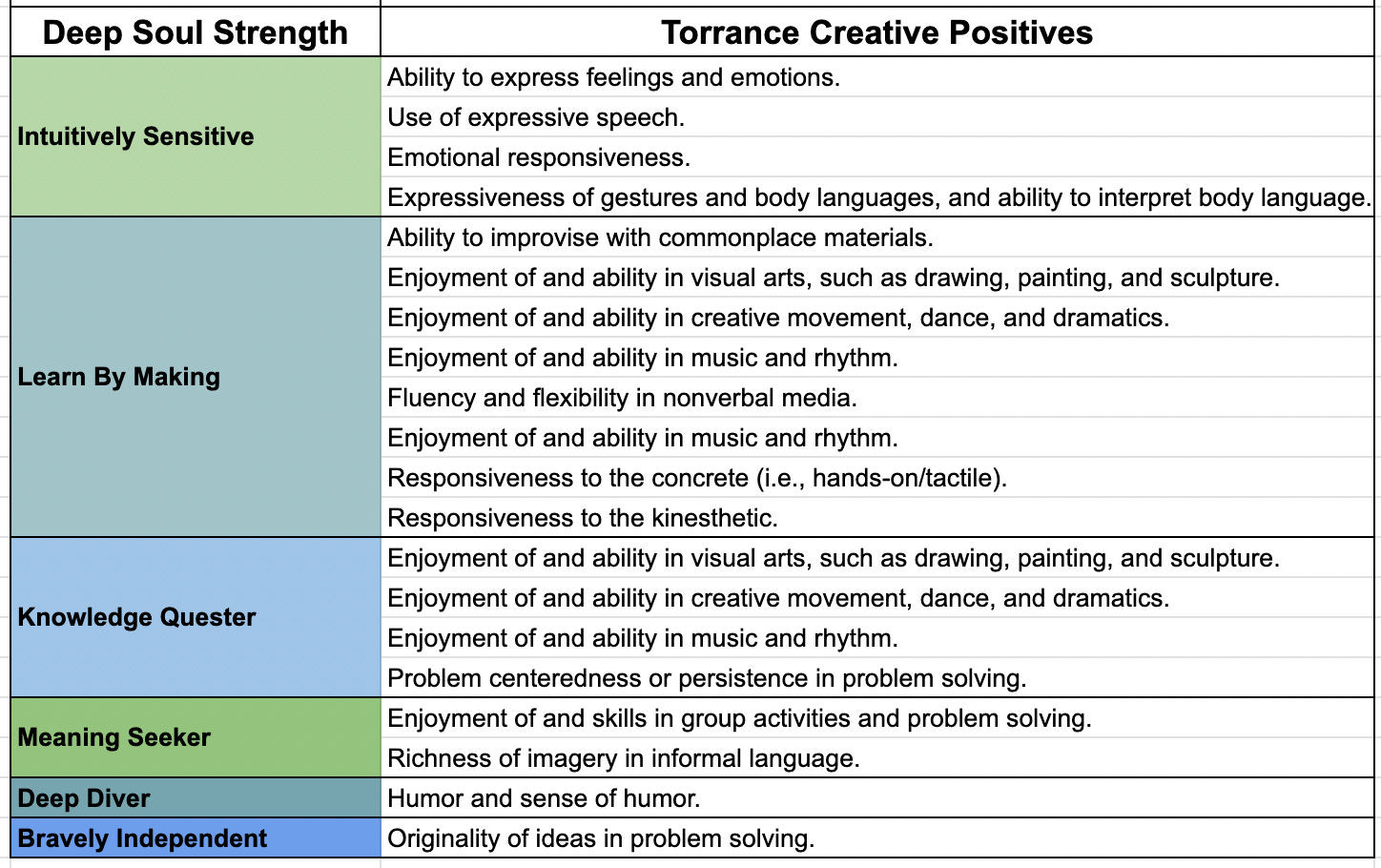

The research and studies around these “creative positives” are foundational to the deep soul strengths. In fact, in the following chart, you will see that each corresponds to a deep soul strength.

Torrance’s Creative Positives list provides a clear set of prompts that teachers and parents can use to spot deep souls at a young age across varied settings, from home to extracurricular programs to school. They can also be used to spot deep soul adults in the workplace or community.

I often observe the “ability to improvise with commonplace materials” in tradespeople and others who have backgrounds more closely associated with the students that Torrance studied. My correspondence with inmates in the US prison system also has shown me that there is a lot of deep soul-searching behind bars, too. Deep soul strengths unrecognized and underutilized can be applied in unproductive ways, but that is a story for another day.

For now, I hope you make use of Torrance’s Creative Positives to find some deep souls!

Discovering and Developing Talents in Spanish-Speaking Students (2012) by Smutny et al., adapted from "Talent Among Children Who Are Economically Disadvantaged or Culturally Different" by E. Paul Torrance in J.F. Smutny (Ed.), The Young Gifted Child: Potential and Promise, An Anthology (1998).

About the art in this post: This aerial photograph entitled “Pier at Sunset” was taken with a drone above the Pacific Ocean by CJ at New Perspectives Aerial Photography. From the artist: “Through my work, I strive to capture unique perspectives of nature and landmarks that could previously only be seen through an airplane window.”